Naples' Rocky Foundation: Jan van Stinemolen's 1582 View

Miguel Fernández ·

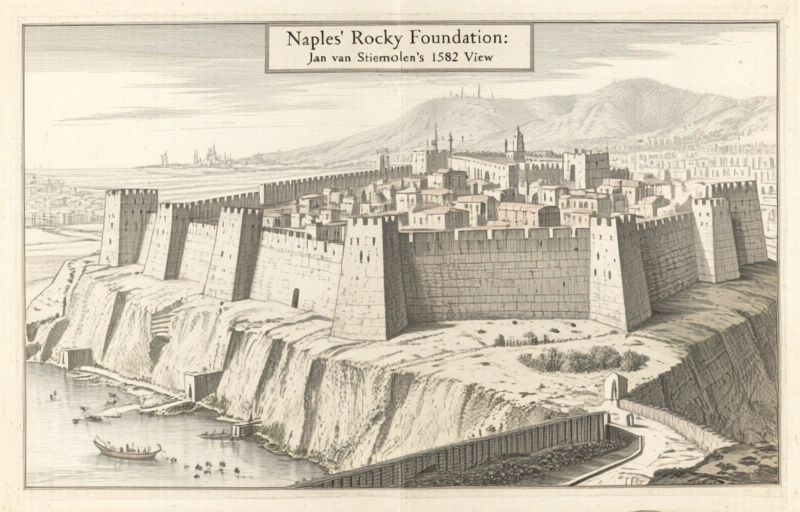

Jan van Stinemolen's 1582 view of Naples offers a unique hillside perspective, blending the city with its volcanic landscape and presenting puzzling architectural details that reveal deeper artistic and naturalist intentions.

Let's talk about a map that changed how we see Naples. Back in 1582, artist Jan van Stinemolen didn't just draw another city plan. He did something different. He climbed up the hillside and looked down toward the gulf. That simple shift in perspective changed everything.

You suddenly see Naples not as an isolated city, but as a place nestled within a dramatic landscape. Vesuvius looms in the distance. The Phlegraean Fields stretch out. Nature isn't just a backdrop here—it feels like the main character, weaving in and out of the city walls themselves.

### The Puzzle of the City Walls

Now, here's where things get interesting for anyone studying urban history. Stinemolen's drawing shows fortifications that don't quite match the official records. We know Viceroy Pedro de Toledo built a specific defensive circuit. But Stinemolen's version looks different, especially in how it connects to the northwestern neighborhoods.

Scholars have debated this for ages. Is it an error? A creative liberty? The question of topographical truth has been a major focus. But maybe we're asking the wrong question.

### The Mystery of the Monumental Gate

Let's start with a specific detail that's always bugged me. Right there in the foreground, Stinemolen drew a huge, impressive gate facing the viewer. It looks important, like a grand entrance. But here's the catch: historical sources say that spot only had a small opening back then, a little passage called a *pertuso*.

The actual grand gate for that area, the Porta Medina, wasn't built until about sixty years later. So what's going on? Did Stinemolen just make it up?

I don't think so. When you look closer, these "inaccuracies" start to make a different kind of sense. They match the visual language people used for ancient, classical towns. It might have been intentional—a way to connect Naples to a grander, older past through imagery.

### Reading the Bedrock

This is my favorite part. Stinemolen didn't just draw buildings. He paid incredible attention to the rocky foundation of the city itself. The texture of the stone, the way it breaks through the soil—it's all there with remarkable detail. You can almost feel the volcanic ground Naples is built upon.

He did this in other drawings too. It wasn't a one-time thing. This emphasis on the bedrock tells us something important about the artist's mindset.

He was highlighting the natural phenomena that make the Neapolitan region unique. At that very time, a new wave of naturalist interest was sweeping through scholarly circles. People were becoming fascinated with volcanoes, earthquakes, and how geology shapes human settlement.

Stinemolen's view wasn't just a map. It was a commentary. He was visually connecting the city to the powerful, unstable earth beneath it.

### Why This Matters Today

So what can we learn from a 440-year-old drawing? Quite a lot, actually.

- It shows us that how we choose to observe a place changes what we see. The hillside perspective revealed connections others missed.

- It reminds us that historical documents can be artistic statements, not just factual records. The "wrong" gate might be telling a deeper truth about cultural identity.

- It demonstrates how art intersects with scientific curiosity. Stinemolen was part of an early naturalist movement, using his craft to document geological reality.

In the end, Stinemolen gave us more than a view of Naples. He gave us a way of seeing—one where city and nature, human walls and volcanic rock, are in constant conversation. That's a perspective worth remembering, especially now.

As one historian noted, "Sometimes the most accurate map is the one that shows us not just where things are, but what they mean." Stinemolen's work asks us to look beyond the streets and see the story in the stone itself.